Share This:

May 13, 2013 | Theatre,

Big Band Boston

With Maurice Hines reminiscing about those who influenced him, we thought we’d stop and do our own reminiscing…on Boston. The Hub has quite the vibrant history when it comes to its legacy of jazz, big band and tap dance. Read on to learn more about Boston’s own tap and jazz greats.

JAZZ

1940s

Perhaps one of the most influential leaders of modern jazz in Boston was Charlie Mariano, famous for his explorative and innovative alto saxophone techniques between 1945 and 1953. He was featured as a soloist in the Nat Piece Orchestra in the late 1940s. In addition to influencing the sound of Boston jazz—single-handedly bringing Charlie Parker’s style of bebop from California—he acted as a bandleader, introducing jazz records of Boston’s greatest talents to the rest of the world.

During this time, many men were returning from serving overseas in World War II. Varty Haroutunian served in the Army Air Force and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Jaki Byard, who had begun his music career at age 15, joined the army before returning to the Boston music scene.

When Byard finished his service in late 1940s, he began touring with Earl Bostic, the jazz saxophonist who majorly influenced John Coltrane. Bostic had been based in Boston. As a jazz pianist and composer (as well as trumpet and saxophone player) Byard gained recognition for his eclectic style which merged everything from ragtime to free jazz.

1950s

Byard made his recording debut with Mariano in 1952; shortly thereafter he joined Herb Pomeroy’s band. He played with them during the mid-1950s and with Maynard Ferguson’s band from 1959-62. Later in Byard’s career, he sometimes fronted the big band Apollo Stompers and he taught at the New England Conservatory, Manhattan School of Music, Hartt School of Music and the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music.

After Varty Haroutunian’s discharge from the Air Force, he studied tenor saxophone at the Boston Conservatory of Music shortly before deciding to tour with Freddie Slack. Once he returned to Boston, he fell in with the beboppers—Byard, Mariano and Serge Chaloff.

Another Boston-educated musician was Ray Santisi, who attended Berklee College of Music in 1954 and became a professor of jazz piano there in 1957. He taught many notable jazz musicians such as Diana Krall, Makoto Ozone, Joe Zawinul, Keith Jarrett and Jane Ira Bloom. He has also taught at Stan Kenton‘s summer jazz clinics on college campuses.

But in 1953, theses forerunners of Boston jazz exerted their greatest influence yet: they created the Jazz Workshop. Mariano served as the founder with help from Haroutunian, Santisi and others. They wanted to offer classes, individual lessons and jam sessions so students could play with professional musicians. In April 1954, Haroutunian, Santisi and drummer Peter Littman took the Jazz Workshop to a jazz club on Huntington Ave nicknamed the “Stable,” where Santisi was co-owner. There, Boston jazz flourished until the building was demolished in 1962.

As a freq uenter of the Stable, Herb Pomeroy decided to put together a big band that drew national attention in the late 1950s. He had begun studying at Harvard University, but he dropped out to pursue a jazz career where he would become an influential swing and bebop jazz trumpeter and educator. He led the band at the Stable from 1957 through the mid-1960s, and then intermittently until 1993. Over the course of Pomeroy’s career, he played with his own jazz bands and musicians such as Charlie Parker and Lionel Hampton. He also backed up singers including Mel Tormé, Tony Bennett, Irene Kral, Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra.

uenter of the Stable, Herb Pomeroy decided to put together a big band that drew national attention in the late 1950s. He had begun studying at Harvard University, but he dropped out to pursue a jazz career where he would become an influential swing and bebop jazz trumpeter and educator. He led the band at the Stable from 1957 through the mid-1960s, and then intermittently until 1993. Over the course of Pomeroy’s career, he played with his own jazz bands and musicians such as Charlie Parker and Lionel Hampton. He also backed up singers including Mel Tormé, Tony Bennett, Irene Kral, Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra.

1960s

Santisi performed with the Benny Golson Quartet in the 1960s. Inspired by the Jazz Workshoppers’ camaraderie, Golson wrote the song “Stablemates” about Pomeroy and Haroutunian.

Just before the Stable’s decline, Makanda Ken McIntyre entered the scene. He earned a bachelor’s degree in music composition from The Boston Conservatory of Music in 1958 with a certificate in flute performance, and a master’s degree in music composition in 1959. He was a prolific musician, primarily playing the alto saxophone but also dabbling in flute, bass clarinet, oboe, bassoon, double bass, drum set, piano and more. His some 400 compositions and 200 arrangements reflect his Caribbean and African American roots, incorporating blues, jazz and calypso. He recorded his first album entitled Stone Blues in 1960, accompanied by local Boston musicians with whom he had been rehearsing for several years. Over the course of his career, McIntyre performed or recorded with many notable jazz musicians, including Jaki Byard, and was a member of the innovative group Beaver Harris 360° Music Experience.

1970s

Then in 1971, McIntyre switched roles from student to teacher when he founded the first African American Music program in the country at the SUNY College at Old Westbury; he taught there for 24 years.

Two years later in 1973, the avant-garde big band The Aardvark Jazz Orchestra was created in Boston, featuring Arni Cheatham as its lead alto saxophone player. Around the same time as Aardvark’s formation, Cheatham helped found the Jazz Coalition advocacy group, and he remained active through the early 1980s. The Jazz Coalition elevated Boston’s jazz profile and gave back to the community through music education programs that encouraged desegregation and brought music to hospitals, homeless shelters, prisons, old-age homes and other underserved communities.

TODAY

Currently, Cheatham is involved in the modern equivalent of the Jazz Coalition—JazzBoston—and another education program, Riffs & Raps.

Ray Santisi has also carried his career well into present day. He has recorded with Blue Note Records, Capitol Records, Prestige Records, Sonnet Records, Roulette Records and United Artists Records labels. In 2005, he released a live album from his regular performances at the Ryles Jazz Club in Cambridge. He has also performed at Carnegie Hall. His band, The Real Thing, has played together for many years, and Santisi has even composed a waltz called Pendulums, inspired by Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz.” In 2008, Santisi was inducted into the IAJE Jazz Education Hall of Fame, and he still maintains his professorship at Berklee.

TAP

1940s

Tap dancing migrated to Boston with performers from New York. Gary Lambert “Pete” Nugent was part of the act “Pete, Peaches and Duke,” regulars at the Cotton Club in NYC in the 1930s, often sharing the bill with other well-known acts such as the Nicholas Brothers. After Pete, Peaches and Duke split up in 1940, Nugent had a solo act “Public Tapper, Number One”. Although Nugent considered himself to be a tap dancer first and foremost, he preferred the style of “all body motion and no tap” rather than “all tap and no body motion.” He graced the floor as a teacher and “tap stylist” at several well-known tap “hot spots” such as the studios of Henry LeTang (who later became a mentor to Maurice Hines), Jerry LeRoy in NYC and Stanley Brown in Boston.

The Stanley Brown Studio became the hub of Boston tap in the 1940s and 1950s, and retained that reputation for decades to come. Dancers flocked from all over to learn his innovative moves in tap and jazz. He became mentor to many successful dancers at the time. When Brown died, Nugent took over the studio.

1950s

Elma Lewis, considered a doyenne of black culture in Boston, was a no-nonsense mentor to generations of young dance, opera and theatre students at the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts. She founded the school in 1950 in her Roxbury apartment before moving it permanently to a former synagogue in the same area. She became a MacArthur Fellow and received a National Medal for Arts in 1983.

1960s

Jimmy Slyde was a tap star to emerge from the Stanley Brown Studio, and came to be known for his musicality, flawless timing and inherent grace. He enrolled in the studio early at the age of 12, where he later met Jimmy Mitchell. Mitchell went by the name “Sir Slyde” and the two developed an act called the Slyde Brothers. They toured the club and burlesque circuit in New England, growing in popularity, and began receiving invitations to perform in big band shows. The Slyde Brothers worked with Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and other great bandleaders of the era. Slyde was an in-demand guest artist on the national and international tap festival circuit.

In 1968, Lewis founded the National Center of Afro-American Artists, a place for art influenced by Afro-American culture, which is still active today despite the closure of the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts in 1986. The tap dancing craze started to die down in the late 1960s as other methods of art were explored.

1970s

On the cusp of this fluctuating popularity in tap was Leon Collins. He began tap dancing in his youth, and worked professionally with groups, partners and big bands. Tap dancing began to fade the 1960s, so until the tap dance revival in the 1970s, Collins restored cars. Then, with encouragement from Tina Pratt and Stanley Brown, he decided to teach, perhaps contributing to tap’s resurgence. In 1976, he opened the Star Steps Studio with “Boston’s First Lady of Song,” Mae Arnette. The studio was located in Roxbury before moving to Brookline in 1982. There it was renamed the Leon Collins Dance Studio Inc. and Collins partnered with several of his students for the project, including Dianne Walker and Pamela Raff.

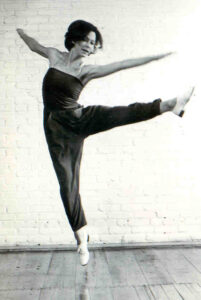

Dianne Walker is also considered a pioneer in the resurgence of tap dancing. She has been dubbed the “Ella Fitzgerald of Tap Dance” and “America’s First Lady of Tap.” She began her dance training in Boston and later studied with Leon Collins, Jimmy “Sir Slyde” Mitchell and Jimmy Slyde. In 1979, she began to dance professionally with the assistance of these esteemed mentors. Her career spans over three decades and through Broadway, television and film.

Pamela Raff was three when she began taking tap lessons; she later studied ballet, modern dance and belly dancing. Renowned tap artist Leon Collins became her mentor when she ended up in Boston in her twenties. She performed with jazz artists such as Gregory Hines, Dizzy Gillespie and Jimmy Slyde. She also co-directed the “Jazz Youth Project” for Boston Public Schools. Collecting accolades over the years, she received choreography awards from Massachusetts Cultural Council, Boston Center for the Arts and New England Foundation for the Arts and a nomination for “Jazz Artist of the Year.”

1980s & 1990s

Leon Collins died in 1985 of cancer, so Raff and other students kept his studio open to maintain his legacy. Raff acted as director for 11 years.

Throughout the 1980s, tap dance made its way back to the movies. Despite being in his early sixties, Jimmy Slyde was cast as a featured dancer in films such as The Cotton Club (1984), Motown Returns to the Apollo (1985), ‘Round Midnight (1986) and Tap (1989)—starring Gregory Hines. Slyde was also cast in the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical Black and Blue (1989). During his solo in that musical, “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” he improvised with rhythms by stomping on the off-beats and simulating the sound of snare drum brushes by scraping his shoes against the floor.

Interested in the sounds of dance, Raff released Feet First in 1995 as the world’s first digital field recording of jazz tap dance with the intent of audiences listening to it.

*****

For all these artists and moments in Boston’s jazz and tap history, we know there are a multitude of others. Who did we miss? What are your favorite stories from the height of this period in Boston? Let us know by commenting on this post…and be sure to see Tappin’ Thru Life: An Evening With Maurice Hines May 14-19 in the Cutler Majestic Theatre!

Leave a Reply