Share This:

September 21, 2013 | Theatre,

The Aftermath of Columbine

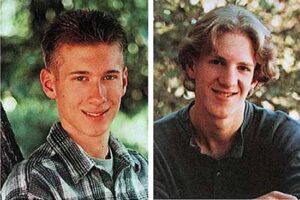

Just after 11am on April 20th, 1999, juniors Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold walked through the doors of Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado armed with a pistol, a rifle and two sawed-off shotguns hidden beneath long black trench coats, carrying a pair of duffel bags filled with propane tank bombs. In the span of about 45 minutes, they went on a shooting rampage that killed 12 students and one teacher, and injured another 24 students, all before turning their guns on themselves. Had it not been for their poor skills in bomb-making, they would have killed hundreds.

The nation stood shocked as it grappled to figure out how two seemingly normal young men could have committed such an act of violence. Columbine became something of a national Rorschach test as the community – and the nation at large – did not hesitate to point the blame on anything they could: violent video games and rock ‘n’ roll culture, bullying in schools, insufficient school security and gun control.

Video Games and Rock n’ Roll Culture

Playing video games for hours at a time was one of Harris’s and Klebold’s favorite pastimes. They were fond of “Doom,” a game licensed by the U.S. military to train soldiers to kill. What makes it so uniquely chilling is that the player does not control the character doing the killing as in most violent video games; instead, rather than having the player see the digitalized “protagonist” on screen, the player is the killer. In a class project they completed only months prior to April 20th, Harris and Klebold made up their own version of “Doom” in which they wore trench coats, carried guns, and killed school athletes. Harris named his shotgun “Arlene” after his favorite character in the game.

Still, video game advocates insisted that video game culture could not be blamed for Harris and Klebold’s actions. They argued that 85 percent of video games are rated “E for everyone,” “E10 plus” or “T for Teen” and that video games have no correlation to violent behavior.

In 2005, independent video game developer Danny Ledonne released “Super Columbine Massacre RPG!” in which players simulate the events of April 20th, 1999 through the perspective of the killers. It caused a national outrage, but Ledonne insisted that it was not meant to encourage mass shootings at high schools, but rather to look at the psychology of the tragedy using video game language. It was discovered, a year later in 2006, that a school shooter in Quebec had played and and favored the game.

Harris and Klebold’s obsession with dark and violent entertainment did not stop at video games. They also were fans of the movie Natural Born Killers (they used the acronym “NBK” to describe the massacre in their journals) and dark, rageful music. Although they weren’t known to particularly love the music of Marilyn Manson, he came under attack after his music was accused in having a hand in influencing the boys. He addressed the accusations in a 1999 Rolling Stone article, saying: “When it comes down to who’s to blame for the high school murders in Littleton, Colorado, throw a rock and you’ll hit someone who’s guilty.” Shortly after the interview he released an album called Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) that contained songs alluding to the massacre. Michael Moore interviewed him for his film, Bowling for Columbine.

Bullying in Schools

Certainly, Harris and Klebold felt like outsiders. They hated the “niggers, spics, Jews, gays, f___ing whites,” the enemies who teased them and the friends who didn’t do enough to stand up for them. Eric grew up in a military family and moved often, made fun of by his peers as he had to start anew at each place. Dylan complained that his older brother and his friends (who were athletic and popular) “ripped on him” and that he felt alienated by his entire extended family – everyone save for his parents – saying they “added to the rage.” They were adamant about not wanting to be included; in fact, they insisted that they were “original.”

When they opened fire in the school, they did not target individuals. It was a revenge fantasy that aimed to indiscriminately take the lives of as many people as possible. They sought fame, wanting to kick-start a revolution for all those who had suffered and been cast out.

It was widely disputed whether or not bullying could be blamed for what happened at Columbine. In 2002, the U.S. Secret Service and U.S. Education Department released The Safe School Initiative, a study that found that “school shooters followed no set profile but most were depressed and felt persecuted.” Since the attack, almost every state has adopted anti-bullying laws, although every state’s policies differ. Spending on school counselors skyrocketed after 1999, rising from $20 million in 2000 to $50 million by 2009. Programs grew to help foster student involvement with school and safety: for example, Shane Jimerson, a school psychology professor at UC Santa Barbara, co-authored a crisis workshop that over 2,000 school employees in about 40 states have taken.

Lax School Security

By far, after Columbine the country saw the most visible difference in school security. These attacks were the catalyst for a school safety movement that was the result, in some places, of paranoia.

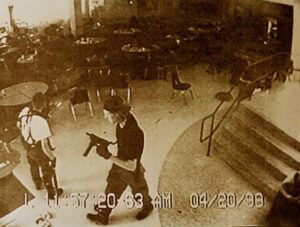

Harris and Klebold caught on surveillance camera in the school cafeteria. They were able to enter campus fully armed without anyone noticing or stopping them.

Schools across the nation locked their doors more regularly, installed security cameras (some even installed metal detectors at the front doors) and mass-notification call systems, stationed more police officers and guards, and required all staff and visitors to wear ID badges. President Clinton signed into law the punishment of a one year suspension for bringing a gun to school. Parents demanded a zero-tolerance approach to school security in the aftermath of the attack as they awaited long-term solutions.

The problem was that zero tolerance meant blurring the distinction between real threats and pranks or unintentional offenses. In Virginia, a teacher called the police on a 10-year-old after he squirted soap gel into a teacher’s water bottle. A 10th grader was kicked out of school for having blue-dyed hair. Schools in four states suspended at least 20 children for the possession of Alka-Seltzer. In Illinois, a seven-year-old was suspended for bringing nail clippers to school. A student even got in trouble for holding a chicken strip as if it were a gun.

As time passed, schools relaxed a little more about security. The U.S. Department of Justice in 2005 got rid of a program that had placed 6,300 police officers in public schools. Years later, the Secret Service reported that the extra security measures taken up by schools after Columbine were “unlikely to help.” In fact, it was found that the increased placement of security guards on campus did little to combat violence but did increase the number of student arrests for minor infractions.

A New Paltz Police officer patrols the lobby of the New Paltz High School in May 1999 just weeks after the Columbine High School tragedy, which took place on April 20, 1999. (photo by Lauren Thomas)

Gun Control

Gun control was not nearly as hotly debated after Columbine as it is now, in the wake of the Aurora and Newtown shootings. However, we can still see similarities in the debates of the past and present.

Harris and Klebold obtained their guns through private sales and straw purchases (today it is even easier – one can get the same guns online without a background check). Shocked that high school boys could purchase arms so easily and harm their innocent classmates, the crippled community demanded tougher gun control legislation in Colorado. The NRA spent $660,000 on Colorado lawmakers to halt the proposed laws, which included background checks at gun shows, the safe storage of guns at home, and an increase in the age for buying a handgun from 18 to 21.

Tom Mauser, who is the father of Columbine shooting victim, Daniel Mauser, stands alongside fellow protestors in Denver in 2010. Photo by Matt McClain

On the national stage, gun control legislation became a major talking point in the 2000 election between Al Gore and George W. Bush. While Bush championed the rights of gun owners, Al Gore cast a tie-breaking vote in the Senate to pass a bill that would require background checks for firearm purchases at gun shows and include safety devices for new guns that are sold. The bill was stalled in the House, however. Although the NRA claimed that after Columbine they were open to stricter gun legislation, they lavished money on a lobbying effort aimed to kill it. Similar legislation introduced this past year did not even make it past the Senate.

Today, 80 percent of guns used in crime are still purchased without background checks through private dealers.

Since the shooting, there have been countless speculations made in attempts to answer the question: how? How can this dreadful event have happened? How could we have prevented it? How can we make sure that it never happens again? It seems that there is no one solid answer, but the least we can do is learn from the past.

Here we are, 14 years and 31 mass shootings later, still learning.

Be sure to see columbinus at ArtsEmerson: The World On Stage SEP 17-29.

Leave a Reply