Share This:

February 1, 2016 | Theatre,

What is an Octoroon?

Read more blog articles associated with An Octoroon!

By 1860, approximately ten percent of enslaved people in the American South had at least one white ancestor, often as a result of forced sexual assault on female slaves by white slave owners. In southern Louisiana, where An Octoroon takes place, there was also a large population of Creole African-Americans, descended from European colonialists in various areas of the African continent. Consequently, free and enslaved people of color could and did look wildly different from one another.

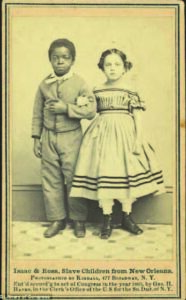

Isaac and Rosa, possibly related former slave children from the same household. This image was used to raise funds for schools serving newly emancipated African Americans.

Legal classifications like “mulatto,” “quadroon” (one-quarter black) and “octoroon” (one-eighth) were used to describe people with lighter skin tones, and these labels were often based on appearance rather than lineage. In An Octoroon, Zoe is given particular preference not only because she is an octoroon, but because she is the biological child of Master Peyton. It was not uncommon for white slave owners to free their biological children, sometimes in their wills, as happens in the play. Even if they weren’t granted freedom, those with lighter skin, particularly young women, were prized highly at the auction and on the plantation. Coveted indoor positions as cooks, drivers or housekeepers were nearly always reserved for lighter-skinned slaves, and in many communities they were treated as a separate class between black and white.

A position in the house did not come without its dangers, though. Light-skinned female slaves, sometimes called “yellow girls,” were highly fetishized and prized as sexual objects, and few made it to the age of sixteen without being molested by a white man. In some parts of the South, quadroons and octoroons were bred specifically for this purpose and sold as “fancy maids”—concubines—to white men. For some enslaved women of color the myth of the quadroon—an exotic, sexually skilled commodity— could mean a path to freedom, a tool for finding a better life. Dark-skinned female slaves did not have this opportunity. They were generally considered less gentle, beautiful or intelligent, and were more likely to be assigned to grueling and dangerous field labor.

Prejudice based on the tone of one’s skin, or colorism, has its roots in this history: dark-skinned women being taught to think of themselves as lower or undesirable, and light-skinned women taught that they are valuable, but only for their sexuality. Though explicit, legally binding prejudice based on skin tone is no longer prevalent, colorism endures today as a form of internalized racism in communities of color.

“I’ve literally heard famous friends of mine who are athletes and have money, when we’re in a club or something, they’ll point to a light-skinned woman and say, ‘I want one of those.’ Now, in their mind, a light-skinned woman is a trophy. A lot of black men believe this, that you get more power, more prestige if a lighter-skinned woman is on your arm,” says Bill Duke, director of the 2011 documentary Dark Girls, which explores the damaging effects of colorism on young African-American women.

Zoe in An Octoroon can never enjoy the privileges of her white family members because she is technically black. She can’t get married, own property or live a free and independent life, and her white neighbors treat her with condescension. At the same time, she is not part of the slave community. She exists in a class in between, and lacks a support network or any real friends. Multiracial children today can face a similar feeling of loneliness. Light-skinned children may be shown preference, considered smarter or more beautiful, but also face accusations of not being “black enough.” Light-skinned and dark-skinned girls alike see that desirable black women on TV tend to be lighter. Dark-skinned girls may resort to using dangerous, unregulated skin-bleaching creams, a $5.6 million industry in the U.S. and even greater in Africa and India. Light-skinned girls may face sexual objectification and fetishization like their ancestors before them. Women from both sides recount childhood stories of bullying, name-calling, even violence. And no one wins. This is to say nothing of the systematic racism and bigotry that comes from outside their community, which children of color must of course also face.

This problematic dynamic is invisible to many. If you haven’t experienced colorism, it is easy to not notice “lightening” products in the cosmetics aisle. You may never think about whether Beyonce looks magically paler on an album cover. But as issues like teen bullying and the representation of beauty in the media are gaining more attention, we would do well to consider an extra component of race and identity with which Zoe and her modern-day counterparts must grapple.

—

Haley Fluke is a Literary Associate at Company One as well as the Co-Dramaturg for An Octoroon.

Sources:

Venus in the Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture by Janell Hobson

The Color Complex: The Politics of Skin Color in a New Millennium by Kathy Russell-Cole, Midge Wilson, Ronald E. Hall

“Q&A: ‘Dark Girls’ to ‘Light Girls,’ Bill Duke talks colorism in new film,” Tre’vell Anderson, Los Angeles Times (1/18/2015)

Colorism in the Black Community: Perspectives on Light-Skinned Privilege

http://www.africanholocaust.net/news_ah/slaveryinamerica.html

[…] a time of “octoroons,” I would have been the help. I may have been allowed to work in the house or even below a […]