Share This:

November 27, 2012 | Theatre,

From Spark to Hologram: A Timeline of Theatre Technology

A figure emerges on the stage. It’s a man dressed in dark clothing. He disappears through a wall. He was never real; he was a hologram.

Such is the magic that we’ve come to accept as part of the modern theatrical experience. Imaginative designing and directing team Michel Lemieux and Victor Pilon have infused their company—aptly titled Lemieux Pilon 4D Art—with this sense of wonder and technological engagement, and they bring it from Montreal to the Boston stage with the ArtsEmerson presentation of La Belle et la Bête.

But the optical illusions so masterfully crafted by Lemieux and Pilon would not be possible without a long history of technology in the theatre. We’ve come a long way from the ancient origins of theatre: performed in daylight with three-sided set pieces turned to change location. Yet some things aren’t quite so new; the Romans made good use of trap doors, moving platforms and changing scenery in their theatres, and the Greeks were infamous for making gods fly in baskets or chariots suspended above the stage.

Whereas the modern effects of defying gravity have advanced, the principles are the same as they were centuries ago. The main difference? Electricity. One spark changed everything. And now, the effects are inescapable. With the internet, Skype and live chat running rampant, it’s easy to forget how we got here. Take a look back at how far we’ve come (or what has barely changed) from the Renaissance till now:

1545: First recorded use of stage lighting design—with candles and torches filtered through vessels of colored liquid. Light from candles is adjusted by stagehands going on stage to snip the candle’s wick.

A theatre worker lights the footlights in an 18th Century European playhouse.

1628: Footlights and sidelights are introduced to the theatre by Joseph Furttenbach. Since the lights are primarily oil lamps and candles, fires break out frequently in theatres.

1750s: Kabuki theatre in Japan uses an elevator stage, allowing full sets to rise and descend to the stage, as well as a revolving stage built into the theatre’s floor.

1803: Robert Hare invents limelight which produced a greenish tint and was often used for spotlights or to suggest sunlight.

1804: Gas lighting is introduced at London’s Lyceum Theatre. Technical illusions really being to take off from this point.

1816: Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street Theatre becomes the first theatre to use primarily limelight for its lighting. Cottons and silks are placed in front of the light to provide various colors.

1860: Paris Opera is using the electric light of a carbon arc as a light projector and follow-spot.

1880s: Electricity becomes widely used in theatres around the world.

1902: Train tracks are used in the staging of Ben Hur for the chariot racing scene.

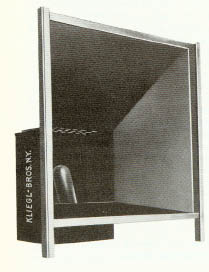

An example of the original Linnebach Lantern.

1910s: Linnebach Lantern becomes the first use of projections on the stage by utilizing a strong light source filtered through a painted glass that produces an abstract, colorful effect.

1924: Erwin Piscator, an inheritor of the Dada movement, uses projected stills in a revolutionary way in his production of Fahnen (Flags) at the Volksbuehne in Berlin. He would go on to share these technical advancements with his future American students at the New School in New York.

1967: Czech designer Josef Svoboda presents Polyvision in Montreal, a production which uses projections on scrims and scenic elements to portray images and film clips while creating lights, shadow and patterns.

1971: Dennis Gabor, a Hungarian- British physicist, receives the Nobel Prize in Physics for “his invention and development of the holographic method.” Although his work occurred mainly in the ’40s, the optical hologram could not become a reality until the invention of the laser in the ’60s.

La Belle et la Bete, playing at ArtsEmerson Dec. 5-9.

1980s: Digital projectors first appear on the market, but are not strong enough for theatrical use—a problem that wouldn’t be solved until the new millennium.

1983: Michel Lemieux and Victor Pilon found Lemieux Pilon 4D Art, beginning a unique tradition of multimedia, multi-disciplinary storytelling over the course of more than thirty productions.

Re: The Pianist of Willesden Lane ~

Beautiful, symmetrically balanced, partially fragmented set. Light glinting off gold framing and moulding throughout – nice! Lovely use of the black box space. FANTASTIC pianist. Compelling story. Clever use of projected imagery within the picture frames. Great music! An enriching experience overall. Thank you for bringing this production to us.

I felt the post-show music was not just unnecessary, it crowded out the live music from the show that was still reverberating within me at the final fade to black. I would rather leave the theatre with the live music from the show working on me than post-show curtain call recorded music. Silence is all we need at the end of the show. That, and the music of audience applause.