Share This:

November 5, 2019 | Theatre, Race and Equity,

Beyond Interpretation: The Language of Isango’s The Magic Flute

The Magic Flute is a title that many recognize, or at least have heard in reference to operatic history, Mozart’s compositions, or even seen it on a marquee as they passed by the theatre. There also often is a certain connotation of inaccessibility attached to classic works, and in opera especially. However, Isango Ensemble’s The Magic Flute opens up a dialogue about language, access, and storytelling beyond words.

“It was very important, I felt, that people in South Africa felt an access to the piece,” explains Mark Dornford-May, director of The Magic Flute. “Therefore if you are performing in a language that’s people’s first language, obviously there is a breaking of a barrier. That continues to be important to us throughout our productions. “

During the Apartheid, the three official languages in South Africa were all Eurocentric, ignoring nearly 80% of people who spoke African languages. For centuries, English, Dutch, and Afrikaans in particular were the only languages permitted in government, education, and even theatre, as a way for the government to systematically disadvantage those who spoke African languages in society. Even today generations of black South Africans refuse to speak Afrikaans because it is considered the language of the oppressor, linguistic scars from the trauma of Apartheid.

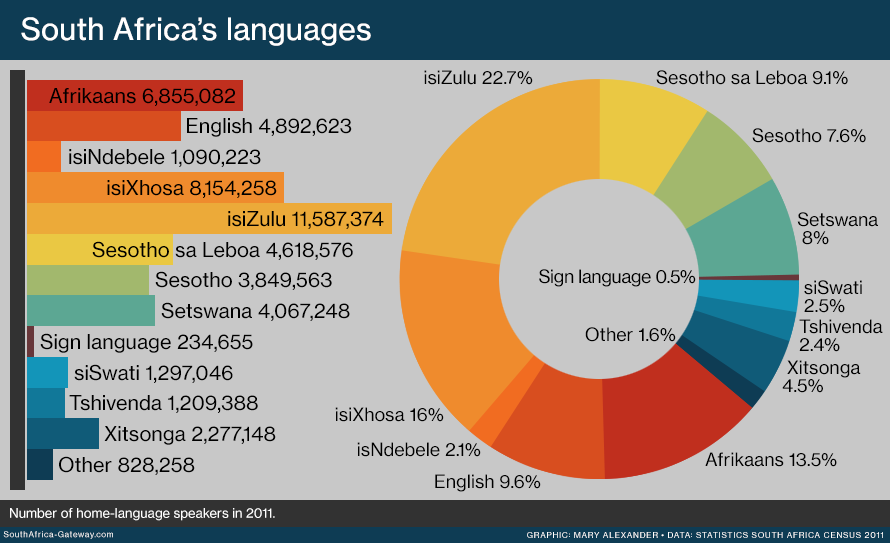

When South Africa established its new constitution in 1996, eleven official languages were named — Sepedi , Sesotho, Setswana, Swati, Tshivenda, Xitsonga, Afrikaans, English, Ndebele, Xhosa and Zulu — as a way to dismantle the Eurocentric oppressive structures and legitimize the languages spoken by the majority of citizens. Today, the population is fluent in at least two languages, the majority speaking Zulu and Xhosa as a first or second language, followed by English and Afrikaans.

Language is culture. Language is lifestyle. Language is literally demographics – where you come from. People are connected by language.

Mandisi Dyantyis, Music Director

However, most theatre in South Africa is still dominated by English. “Part of our mission is to help break that down and open up theatre to all the different language groups within the country. I don’t think we’ve ever used eleven in the same piece, but we’ve used all eleven over the last 20 years in some way,” say Dornford-May. “Even Afrikaans. We use it occasionally in our productions because I think its important to offer a hand out to other groups and try to build bridges across that past.”

When we presented The Magic Flute in 2015, music director Mandisi Dyantyis articulated perfectly, “Language is culture. Language is lifestyle. Language is literally demographics – where you come from. People are connected by language.”

Because the politics of language in South Africa is still tenuous, the various languages are not used to dictate a certain type of character in Isango’s work. In their version of the Mystery Plays — a sort of retelling of the Passion Plays — both God and Lucifer spoke all eleven languages. No one South African language was supremely good and no one language was supremely evil.

When translating The Magic Flute, the original text was first translated from German to English to set a common ground of understanding and then the ensemble begins the process of adding in other languages. “What we’ve developed is finding a way of translating certain sections but still allowing the narrative to flow even if you don’t fully understand the language thats being spoken,” Dornford-May explaining the process. “For example if I say ‘What color is this table?’ in English, the next line in Xhosa would be ‘the table is grey’ so you know what the question was. People follow it in that way.”

This method of translating still allows audience members who speak maybe just one of the languages included in the production to understand the narrative, especially since all Isango pieces are presented without surtitles. However, language is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to performance.

“People communicate in so many different ways and language is very much the final part of that communication. So often people come out of the theatre after pieces we’ve done and talk about a certain line and how funny it was. Now, I know they didn’t understand the line at all, but they feel they did because they saw what was happening on stage,” Dornford-May reflects.

The history of language in South Africa is an integral part of Isango Ensemble’s work and we are grateful to have productions that not only bring that history with them, but broaden the power of theatre.

“You may not understand all the words, but the music, the movements will you tell something,” Dyantyis says. “If you can take something away from this experience that means something to you, without fully understanding it, that is what we want for you. That is the power of art.”

Join ArtsEmerson for The Magic Flute NOV 06-10 at the Cutler Majestic Theatre for a revolutionary act of opera, full of joy and celebration.

Leave a Reply