Share This:

March 21, 2012 | Theatre,

Café Culture History, Part 3: Café Culture and Public Spaces

By Magda Romanska

American scholars have long noted the comparative scarcity of informal public spaces in American social and cultural life. In the last few decades, the public sphere, parks, streets, squares and walkways have become the domain of the poor and the homeless. Many sociologists lament that, increasingly, Americans are expected to find respite, entertainment, companionship, and even safety almost exclusively within the privacy of their homes (with mega mansions – featuring tennis courts and movie theatres – built specifically to cater to every potential social need). Historically speaking, European-style cafés never really took root in the U.S. In the 1950s, for example, while Paris had thousands of sidewalk cafés, New York had only three (one for every three million people). Some scholars blame this scarcity on the size of American cars (larger cars required wider streets, which in turn meant narrower sidewalks); others suggests that it is the American culture of productivity and efficiency that discourages idle coffee house chit-chat.

American coffee houses have been mostly modeled on the typical Italian espresso bars, which are foremost fast and functional. With few tables and no stools, they discourage large and prolonged gatherings. In the last two decades, American coffee house culture has become dominated by chain stores, with Starbucks becoming the most successful model of commodification of the European coffee house experience. Chains like Starbucks attempt to replicate the traditional coffee house’s unique artistic and intellectual atmosphere, albeit all the stores play the same music, have the same interior design and offer the same selection of snacks and coffees.

Modern architects and sociologists classify cafés as the ‘third place’ – with home being the ‘first place’ and work ‘the second.’ The ‘third places’ play an important social and psychological role, providing respite from the two spheres of personal responsibility while at the same time offering the individual a deeper sense of communal belonging. The third spaces are also essential for democratic process and civic engagement. In his famous book Bowling Alone (1995, 2000), Robert Putman notes that the lack of third spaces in American social life contributes to decreased participation in the civic processes. Likewise, another American scholar, Ray Oldenburg suggests that the absence of an informal public sphere creates social and psychological isolation, straining family and work life as it places too much pressure and too many expectations on these two spheres to provide it all. Without the third space in which to relax and forget, if only for a moment, our work and home troubles, we have no release from the constant pressures and anxiety of everyday life …

Modern architects and sociologists classify cafés as the ‘third place’ – with home being the ‘first place’ and work ‘the second.’ The ‘third places’ play an important social and psychological role, providing respite from the two spheres of personal responsibility while at the same time offering the individual a deeper sense of communal belonging. The third spaces are also essential for democratic process and civic engagement. In his famous book Bowling Alone (1995, 2000), Robert Putman notes that the lack of third spaces in American social life contributes to decreased participation in the civic processes. Likewise, another American scholar, Ray Oldenburg suggests that the absence of an informal public sphere creates social and psychological isolation, straining family and work life as it places too much pressure and too many expectations on these two spheres to provide it all. Without the third space in which to relax and forget, if only for a moment, our work and home troubles, we have no release from the constant pressures and anxiety of everyday life …

In The Lonely American, Jacqueline Olds and Richard S Swartz warn that “increased aloneness” and “the movement in our country toward greater social isolation” are detrimental to our health and well-being. However, in a recent issue of Time, Eric Klinenberg, professor of sociology at NYU, argues that the increased isolation actually contributes to the reemerging need to reconnect. Klinenberg notes that “the evidence suggests that people who live alone compensate by becoming more socially active than those who live with others and that cities with high numbers of singletons enjoy a thriving public culture. Paradoxically, living alone might be exactly what we need to reconnect.” Does it mean that we are on the verge of new Café Culture Renaissance?

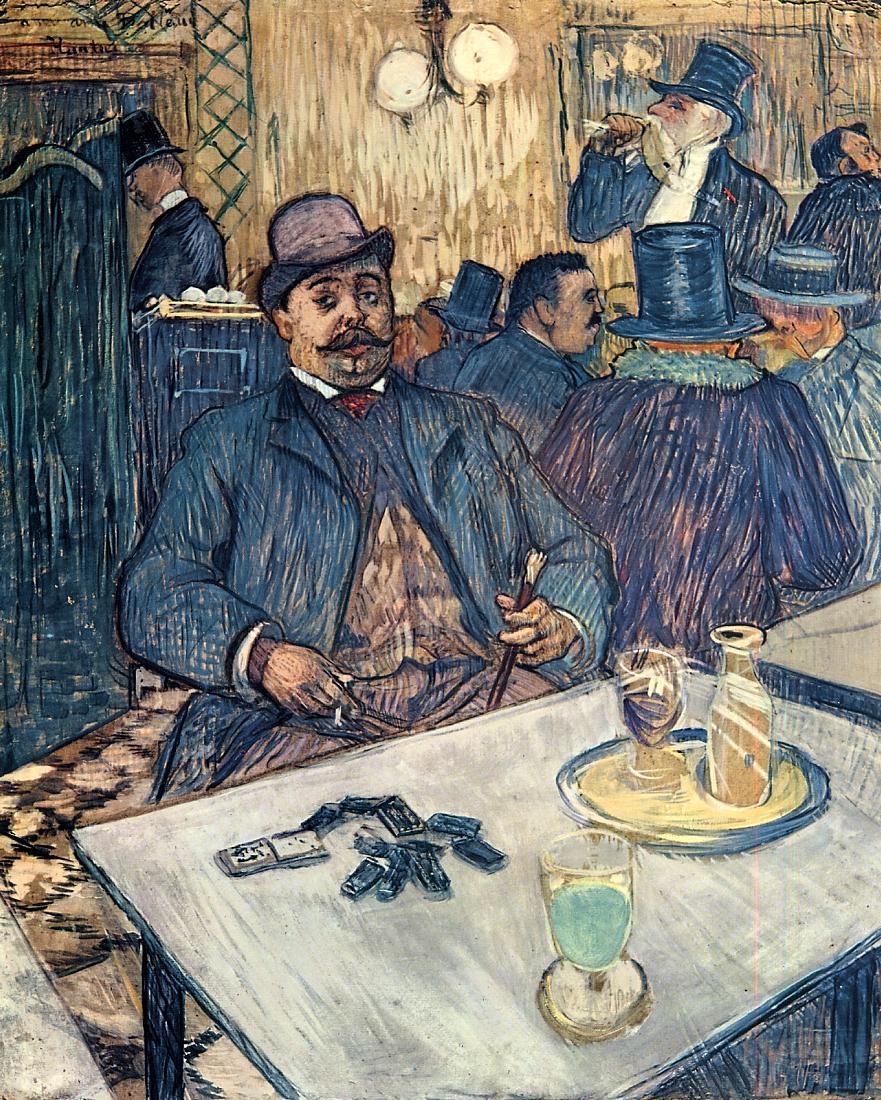

Image 1: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Monsieur Boleau in a Café , 1893

Image 2: Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) Café Scene no. 1

Image 3: Juan Gris, Mann in the Café, 1912

Images courtesy of Google, the Yale Beinecke Library, the Harvard Via Collection and Artcyclopedia.com

Leave a Reply