Share This:

March 22, 2012 | Theatre,

Café Culture History, Part 4: Boston

By Magda Romanska

Boston has always been the trendiest town in the U.S. and when it comes to coffeehouses, it’s no exception. Although the first man known to bring knowledge of coffee to North America was Captain John Smith in 1607, who was familiar with coffee, thanks to his travels in Turkey, the first-ever coffeehouse in America was actually opened in Boston by John Sparry. As Boston city records indicate, in October 1676 John Sparry was “aproued of by the select men to keepe a publique house for sellinge of Coffee.” But even before Sparry opened his first official coffeehouse, “Dorothy Jones was the first to be licensed [by the city of Boston] to sell ‘coffee and cuchaletto.’ This license is dated 1670, and is said to be the first written reference to coffee in the Massachusetts Colony. It is not stated whether Dorothy Jones was a vender of the coffee drink or of ‘coffee powder,’ as ground coffee was known in the early days.”¹

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Boston was the metropolis of the Massachusetts Colony and the social center of New England, so it is no surprise that the most prominent coffeehouses were established here in Boston. Boston coffeehouses were “generally meeting places of those who were conservative in their views regarding church and state, being friends of the ruling administration. Such persons were terms ‘Courtiers’ by their adversaries, the Dissenters and Republicans.” The coffeehouses also functioned as meeting spaces for business, politics, theatre, concerts, exhibitions and other secular activities.

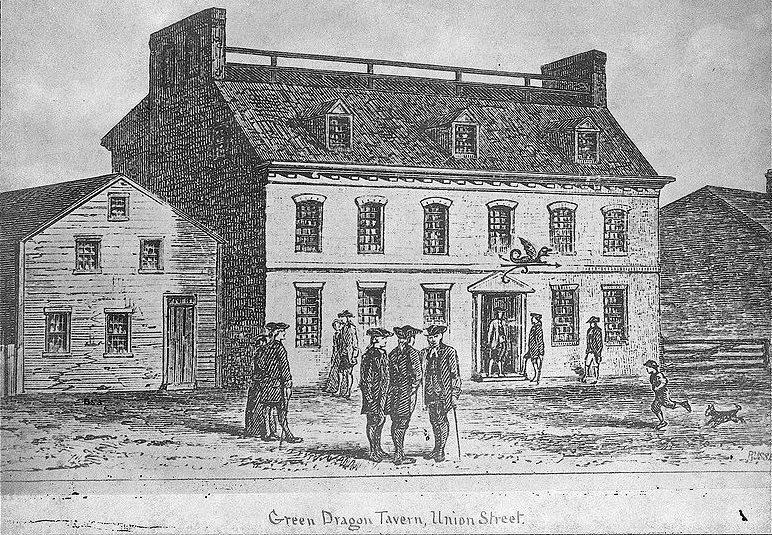

The Boston Tea Party of 1773 was planned in one such coffeehouse, the Green Dragon, known by historians as the “Headquarters of the Revolution.” Located at that time on Union Street in Boston’s North End, the Green Dragon was a meeting place for the Freemasons, who used the first floor. The Green Dragon’s basement was used by several secret Revolutionary groups. The Sons of Liberty, the Boston Committee of Correspondence, and the North End Caucus each met there. The Boston Tea Party was planned there, and Paul Revere was sent from there to Lexington to warn the  Revolutionaries about the approaching British army. In January 1788, a meeting of the mechanics and artisans of Boston that took place in the Green Dragon passed a series of resolutions urging the adoption of the Federal Constitution. Although the building was demolished in 1854, the current Green Dragon Tavern is located at 11 Marshall Street in Boston’s North End. Its website proudly proclaims that it is the “headquarters of the Revolution.”³

Revolutionaries about the approaching British army. In January 1788, a meeting of the mechanics and artisans of Boston that took place in the Green Dragon passed a series of resolutions urging the adoption of the Federal Constitution. Although the building was demolished in 1854, the current Green Dragon Tavern is located at 11 Marshall Street in Boston’s North End. Its website proudly proclaims that it is the “headquarters of the Revolution.”³

The Boston Tea Party was itself a resounding vote in favor of coffee. The citizens of Boston, “disguised as Indians, boarded the English ships lying in Boston harbor and threw their tea cargoes into the bay, cast the die for coffee; for there and then originated a subtle prejudice against ‘the cup that cheers,’ which one hundred and fifty years have failed entirely to overcome.”¹

The famous Boston Exchange Coffee House (1809-1818) was a hotel, coffeehouse, and place of business in the early nineteenth century. Designed by architect Asher Benjamin, it was located at Congress Square, on Congress Street, between State and Water Streets. In its day the seven-story colossus was the largest building in Boston and one of the tallest in the northeastern United States. The Exchange was built by Andrew Dexter, Jr., a pioneer real estate speculator, financier, swindler, and confidence man, who amassed an enormous fortune through the nation’s first bank-lending scheme.

In the 1790s, at a time when paper money was still treated with suspicion, Dexter manipulated a string of real estate deals, building a fortune for himself. “In January 1807 he announced in the Boston Gazette his intention to build … ‘an elegant Exchange and Hotel in this metropolis,’ which he declared ‘utterly deficient in those public conveniences, which are usually attached to every city of trade in the world.’ The proposed Exchange Coffee House would ennoble Boston’s commerce, then conducted largely outdoors. Dexter anticipated that the Coffee House would cost one hundred thousand dollars, a staggering sum. But, he insisted, the rents from its offices, function halls, brokers’ desks, hotel rooms, and other services would allow shareholders a healthy return on their capital.”² But in early 1809, just as the Exchange was about to be unveiled, Dexter’s scheme collapsed. As a result, “in Boston, the exchange became an opulent but largely vacant building, a symbol of monumental ambition and failure.”³

On November 3, 1818, a giant fire destroyed the seven-story Exchange Coffee House and it burned to the ground. Its financial backers, including Gilbert & Dean, lost thousands of dollars, which they never recouped. The story of the building is included in the book The Exchange Artist: A Tale of High-Flying Speculation and America’s First Banking Collapse, by Jane Kamensky.

Today, Boston coffeehouse culture is as thriving as it was at its origins. The city boasts hundreds of coffeehouses and street cafés, from upscale to artsy, from sophisticated to grungy. The Boston Area Coffeehouse Association (BACHA) was founded in May 2000 to help independent, non-profit coffeehouses in the greater Boston area, to increase communication between the various coffeehouses, and to help to promote local musicians.

To find a coffeehouse near you, to look up the coffeehouse performance schedule, or to take a virtual tour of some of the BACHA coffeehouses, visit http://www.bostoncoffeehouses.org/

Image 1: Green Dragon Tavern on Union Street, established in 1714

Image 2: Green Dragon Tavern today. The establishment takes pride in its heritage.

Image 3: Green Dragon Tavern on Union Street, 1773

Image 4: The Exchange Coffee House,1812

Image 5: Exchange Coffee House, Boston, Massachusetts, United States, 1808

Image 6: The Exchange Coffee House, ca. 1848

Image 7: The Exchange Coffee House location, 1812

Image 8: “Conflagration of the Boston Exchange Coffee House” by J.R. Penniman, 1824

Image 9: Original vintage magazine print ad for Shawmut Bank featuring the old “Exchange Coffee House” in Boston, 1940

Image 10: New England Coffee House, Clinton Street, Boston MA. Bowen’s Picture Of Boston, 1838

Image 11: Lamb Tavern, Drake, 1917

Image 12: Commercial Coffee House, corner Milk St. and Batterymarch St.

Images courtesy of Google, the Yale Beinecke Library and the Harvard Via Collection

Leave a Reply