Share This:

April 30, 2014 | Theatre,

The One-Woman Show: From the Heart to the Head

Sometimes in all of the crazy coming and going of artists at ArtsEmerson we find themes that crossover multiple productions. This spring we have two one-woman shows that lend themselves to an interesting conversation. The day after The Wholehearted closed as Sontag: Reborn appeared on the horizon, Polly Carl, Director/Editor of HowlRound, held a conversation between Suli Holum (The Wholehearted) and Moe Angelos (Sontag: Reborn) about finding their characters and creating worlds around them.

Polly: Suli, you just closed a show for ArtsEmerson, The Wholehearted, in which you play a working class female who has risen to acquire some fame and at the height of her career is stabbed and shot by her husband who is also her trainer, and Moe you’re about to bring The Builders Association show Sontag: Reborn to ArtsEmerson to open next week where you play Susan Sontag. Both shows are solo shows. I wonder if you could start our conversation perhaps talking about the demands of the solo show as a performer, and then talk a little bit about your preparation for these different parts.

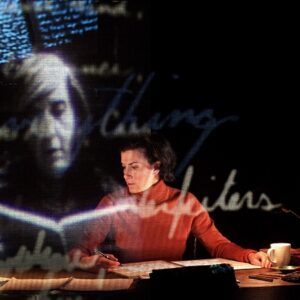

Suli Holum in The Wholehearted.

Suli Holum in The Wholehearted.

Suli: The way that our process works is that the role doesn’t exist until the end, so rather than an idea of something I was trying to prepare for, I sort of dove into a bunch of research and then the character emerged over a course of a two-year process. The research and training were mostly centered around boxing because we knew that this woman was a boxer. So there’s the rigor of that physical training. We also knew that there was singing, so I did some Fitzmaurice voice training and some work to free my voice and get unafraid and a little messy with my sound. And then my other preparation was in meeting the world of boxing, the people in boxing, and then a bunch of other varied resources like author Cheryl Strayed was a big influence and Nicholas Cage. It’s a funny combination of things.

Moe: So Suli, you have a deeply physical part and I have a deeply intellectual part. To even consider playing Susan Sontag, who was of course a real person who is within living memory of many, many people especially in New York, that’s a daunting task. I feel kind of lucky that I did not know her personally because it’s very freeing when there isn’t a person or the person doesn’t exist now. Of course I can look at films of her, but what I did was read a lot. Really a lot. She was a writer, of course. I can’t say I read everything she wrote. That would take a very long time, but I certainly read everything from the period of the play, which is the early sixties into about 1965 and that’s a lot. And her journals. The show is based on her journals. I really combed those over as well as going to her archives at UCLA and looking over the notebooks themselves and the masses of ephemera and correspondences and juvenillia. That was really a wonderful experience. And in terms of actually performing the part, my huge task is memorization, you know? It’s a lot of text and it’s not spoken language. So first, how to memorize it and be able to say it all reliably, and then how and what do I say—do I speak text that is not supposed to be spoken language? There’s a lot going on there.

Polly: There is a lot. Moe you just alluded to this, but these two women couldn’t have more different makeups. Dee Crosby is a fighter. She’s all physicality and emotion and Sontag is all intellect. And I just wonder, maybe Moe you could start here, what parts of yourself as a performer and a person did you discover becoming Sontag?

Moe: It’s a curious puzzle and question for performance, because I don’t think about it like I am becoming Sontag, but I do think about becoming her journals, which is slightly different. I’m playing the Journal and not necessarily her, and that is because of the language structure of the text—it’s nothing close to my speech right now, our speech together, or dramatic speech. She’s very dramatic, don’t get me wrong, you know she’s a tortured teenager at the beginning of the show with big emotions, but I have to hit this tone—tone isn’t the right word—but this place in my speech which is alive, animated, but it is also delivering a lot of intellectual information, which is often pretty tough to read on the page. So for an audience listening to that text, it’s really different and it’s challenging.

Polly: The challenge of the language itself is a fascinating way to describe it, becoming the Journal versus becoming Sontag. How about for you Suli, what things did you uncover as a performer and as a person as you entered Dee Crosby? Certainly you weren’t a boxer before you started this process, so that’s one thing.

Suli: I can’t separate the work from the way of working, because I’m really fascinated by how things get made and who is in the room and how that affects what the audience ends up seeing in the end. This was a really interesting process for me and Deborah [Stein] because in order for me to become this person I had to enter into quite a bit of chaos, but I’m also co-directing the piece. So the process of how to structure a rehearsal process that allows me to go deep into that exploration and be in that place and then be able to step out and dig and sift through what we were making and mine it and carve it and shape it and extend that to the rest of the creative team was a big challenge and a huge growth experience for me. It really can be summed up with me getting better at asking people for help. I didn’t understand going into it that this process of becoming really tough, this idea of this woman, this boxer, this fighter that she is way, way tougher than me, and that in order to bring her to life, I had to become much more vulnerable as a person, as an artist, as a creator, and it’s been great. It’s been epic.

Moe: Can I just say something about toughness?

Polly: Yes, please!

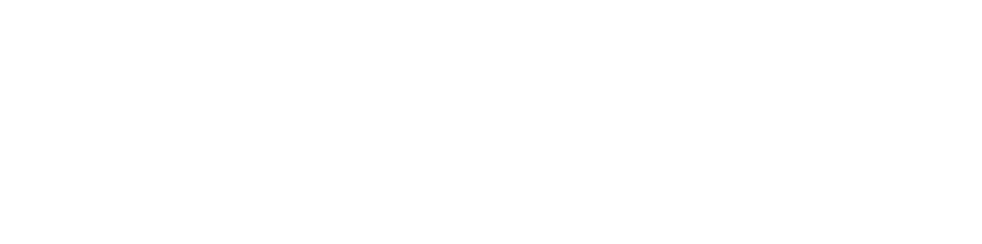

Moe Angelos in Sontag: Reborn. Photo credit James Gibbs

Moe Angelos in Sontag: Reborn. Photo credit James Gibbs

Moe: Sontag too was very tough not physically, but intellectually. She was an extremely rigorous thinker and for myself, I had to become rigorous in that way, in my thought process and in not settling. Marianne Weems, my director, and my designers made something beautiful—visually, aurally, physically beautiful in a way that Sontag was tough in that aesthetic way that I’m not. So that’s where I had to get a little tough.

Suli: Moe, you say that Sontag was not a fighter, but I think of her as being a fighter. Not with fists, but she doesn’t back away from conflict.

Polly: She could slice you and dice you with language in a way that Dee could slice you and dice you with boxing. Very different, but similar.

Suli: Yeah, totally!

Polly: To that question of toughness, do you think there are particular expectations of how a female performer owns the space on stage alone?

Suli: This is the third solo performance I’ve created for myself in my career, and from the very first, I wanted to grapple with the form. I have a lot of issues with much of the solo performance I had seen, feeling there was something inherently not theatrical about it. A lot of it felt limited, like sitting on a stool telling your personal stories version. I was very excited by the prospect because I love working from structure and limitation. If all you get is one performer, how can you do impossible things? How can you do all the things you think you can’t do with only one performer? And that’s where I’ve always tried to work from. I’m not really answering the gender question, but along the way, I have also thought in addition to grappling with the form, because it’s a solo show, it’s lean and mean. I can be very pointed about what it is that I want to say. It’s really been an exciting process to look around me and notice what’s missing in terms of story out there. And of course I’m a woman so I’m looking at stories about women. And this tragic, flawed, violent, self-destructive character that I play in this show is something men have done to great acclaim for a long, long time. I was really curious to see if a woman took an audience on that journey and where would they be willing to go with me?

Moe: I guess there is some central question always of what space women occupy on stage. Can we even do it? I don’t know. I feel confident, yes, but when you look at popular culture, you have to question that. I think that always I’m trying to make the female a universal in the same way that Hamlet is universal. There are so many things that are left unsaid about our experience as women on this planet. Just as a little anecdote, after a show one night at Sontag, a friend said to me, “It was just so great to see a woman on stage being smart.” That was a lovely compliment, but also deeply tragic to me that that’s the fucking case, but it is. We don’t see that. But hey, if that’s the little piece of work the play is doing, great!

Polly: Yeah, someone emailed me after The Wholehearted saying it was an archetype on stage they hadn’t seen before, and you’ve heard something similar about Sontag, and here we are sitting in 2014 and we haven’t seen certain kinds of women occupy the stage in this complete way before. It’s quite striking to me.

Suli: I love that you brought up this idea of universal stories because it’s something I’ve really been grappling with as a maker, I’ll get started on a project and then a little ways in I’ll get worried that it’s too narrow. Maybe it’s something that’s only interesting to me? We threw Wholehearted out there thinking a little bit that we don’t know if we are going to find our people. And then the first week of performances, we got to perform for some of the most diverse audiences we had ever performed for, racially and economically diverse, and there was a real palpable sense in the theater that there were people there who don’t usually go see plays. That made me think about when we talk about our universal story in a play, what universe are we talking about, because who goes to see plays? Who are the critics who write the reviews of plays? That’s a small universe. That’s a really valid thing to be grappling with as an artist—the goal of telling universal stories and what that can mean or should mean.

Polly: So you’re both dealing with various other characters who live inside the play. In the case of Dee Crosby, you’re contending with Charlie Flaxon, her abuser, and Sontag has her ex-husband Phillip Rieff. But you’re also both dealing with obsessing about another woman—Carmen for Dee and Maria Irene Fornés for Sontag. Can you talk a little about obsession and where you access obsession as a performer?

Moe: Sontag was a very passionate person, so she could really dig down deep into something, go very, very far down the rabbit hole, and that includes her romantic passions as well. It’s interesting because, again, from people who saw the show, I got many comments like, “I didn’t think she was so passionate,” or they didn’t think she was so emotional. You know, she had a very constructed public persona and she was a deeply private person, so why would people know that about her? But I think it’s very beautiful, actually, her willingness to go emotionally into a far place, in her love and in her obsessions. Because her obsessions were also things like film—I mean the woman went to a movie every day of her life, practically, if not several. For me, well, I don’t know, I guess anyone who chooses a life in the theater has to have some kind of strong drive to do that. So I guess that is my personal obsession. It’s just one or two clicks over to fuel that into whatever part I’m doing, because you know Polly, it might surprise you, but it’s not about the fame and the money.

Suli: I think for me it’s the desire to be all in, to be consumed by something. I feel like that’s the driving desire that keeps me making. And it’s taken me time, a lot of time. I started making theater when I was really still a kid, and then growing into an adult and having a life and responsibilities and family and all kinds of things that help me feel grounded and important and relied upon. And then also always having this desire to just completely dive into something and get consumed by it completely. I didn’t realize Sontag’s journey began with her as a teenager in your show, because it’s the same in ours, that we meet the teenager, and that’s where the real love starts in The Wholehearted—that place of just raw yearning like before you even know how to cover it up yet, you’re just a mess. For me, it was just time for me to revisit that place, a very sweet place. And when it comes up in our piece, people get to the point where they’re actually really grateful for it. Because there is so much aggression and difficulty for this woman and when she reveals that part of herself, there’s a bit of relief, it’s palpable. Even though it’s not simple and it’s not necessarily happy, it’s just a true and open place.

Polly: We had a great moment at the bar after one of the final performances of The Wholehearted talking about when we first experienced desire, speaking of obsession.

Moe: We hear all about it from Sontag.

Polly: Exactly! It’s so great in Sontag, we get exactly the moment she intellectualizes this desire, which is really wonderful.

Suli: And that’s universal, right? I mean do you feel like you get a response from the audience with that material where everyone responds to it? Or do you feel like women respond to it differently than men?

Moe: That’s a really good question. I think people respond to it, and like I said earlier, they’re surprised by it, because of what her public persona is perceived as. But she’s also sixteen and in love, you know? The title of the first volume of journals is Reborn and she says, “I am reborn in the time, retold in this notebook.” She wrote that on the inside cover of the notebook after she had finished the notebook. Like she understood that this thing deeply changed her. And she’s very articulate about it. I was not articulate about it, I was a mess. And she’s a mess, but she can say that, she can say it very beautifully, actually.

Polly: Both of these shows work with just stellar video design and so you’re both interacting with your own performance being perceived and you’re also both being seen on camera in different ways. I think the impressive nature in both these shows is the way that this is seamless and wonderful. I wonder as performers if you’d talk about those kinds of challenges engaging video elements while you’re on stage as you’re being seen in those two different mediums at the same time.

Suli: I think the challenge for me working with video was not a performer challenge, but a creator challenge. Then over the course of time to figure out how the presence of the camera and the screens and the placement of the screens were a part of the story and a part of the action, as opposed to icing on the action or a decoration. I feel like just in the last couple of weeks at Emerson, we finally really cracked that, but it was a long time in the making.

Moe: Well, always with Marianne [Weems], her rule of thumb is, “what is this media doing here?” and “is it part of the dramaturgy of the piece?” In other words, is it taking on a storytelling function. Sure, you can make really pretty, beautiful scenery using projections, and that’s totally valid, but it’s more interesting if the video is one of the storytelling tools, right? If it’s showing us something we couldn’t see otherwise, and that something is necessary to the story. That’s a more rigorous problem to solve in media, and in Sontag it’s interesting because there is a live camera above the desk, but it’s a static shot, right? I don’t ever acknowledge that camera or play to it. It’s kind of just a slightly pervy voyeur, it’s just looking at what I’m doing on the desk, and that’s in a rear projection behind me. And then there’s this projected image of Old Lady Sontag, of Sontag who we think of when we think of Sontag, or I do anyway, older Sontag that is in front of me on a front projector, and I relate to her, in a live sense, in the moment. But I’m not playing to live cameras like your piece, Suli. It’s interesting that the camera is just observing, and Sontag, of course, had a lot to say in her own work about the lens and what it is seeing and how it is seeing, and what does that seeing do to our consciousness. The media is demanding in other ways. Suli, I’m sure you can speak to this as well, you must hit your mark. It is very technical. You must be in this exact space at this exact time or else you’re not in the scene. Sometimes it’s more like being in a film than being on stage in a piece of theater, it’s a combination, it’s a weird hybrid. But that media absolutely amplifies my performance.

Suli: Something we were really hoping for with our piece, which we got to see play out, finally, with audiences, is that there would be a couple sitting next to each other and one would be watching the action on stage and one would be watching the Jumbotron. Two people right next to each other. Our goal was to create an experience where people could choose their own way through. And also it’s in the round, so there’s just so many potential perspectives on what’s happening.

Polly: A last question—almost all of my questions reveal that I am not a performer, but this one will particularly reveal that—there’s a kind of awe with which I watched both of these performances. I feel like I’m fully with you, in the reality of it. You are both so engrossing. Moe, you’re coming back to doing this piece after a break from it, and now you have to jump back into being the Journal again. And Suli, you’re walking away from embodying this person. And I just wonder, how does a performer go back and forth between being in and out of that kind of all-encompassing space?

Suli: I’m sitting here, and I don’t have to do it for a while, and my neck is totally in spasms, and my body is like “Thank god you’re not doing this for a while,” you know? Because when I’m in it, my body’s like, “let’s do it, let’s do it, we’re gonna do it,” right up until the very last minute. Pushing through. This show I will need to find a way to keep alive in my body somehow. Because if I put it away completely, then I’m going to have to start all over again physically, and it did take me a year to get where I am right now.

Moe: I guess it’s the same for me, except it’s a lot of just trying to hold onto the text mostly. Because it’s a lot of text. And my brain is not as elastic anymore. It just really requires a lot of effort to memorize things. So I don’t want to have to start over, but I’ve had a couple of breaks. We did the show last June, then I did it in October, now I’m doing it again, so there’s been these six-month gaps, six to eight months. I do have to work at getting the text back functionally in my head, so that I have very quick access to it. It’s a lot of talking, so I try not to talk as much—I’m a talker—but I try not to talk as much on show days, because I have to talk for an hour up there. As they say in the business, “vocal rest.”

Suli: Do you find that when you put it away for a while, and then you come back to it—you make a show, and then it lives in repertory so you get to come back to it, and I love that experience so much, it’s so different from other plays that get done. When you come back to a thing you haven’t done in a while, it shows you how you’ve changed in the meantime, and there’s this way that you find things in it that you, I guess because you’ve changed, you couldn’t have found before.

Moe: Absolutely. So often, I’ve had this experience of coming back to something, and thinking, “oh, oh that’s what I meant, that’s what she meant, that’s what it meant,” you know, to have a different depth of understanding of something I’m saying or doing, even though in many cases I wrote that thing, but it’s very strange to have a different understanding later on down the line, but it’s true, it happens.

Polly: Moe, we can’t wait to get you here, and Suli, we can’t wait to get you back. Thank you both.

WHOLEHEARTED is unlike anything I’ve seen … raw yet meticulously and precisely performed. Suli Holum makes us fall in love with one of the great female characters of this new century.